British Egyptian Film-maker on the revolution, change and mental health

Photo credit: ‘Egyptian Revolution’, Cairo, Egypt

A few weeks ago, I caught up with British-Egyptian film-maker friend Mohammad “Mo” Homouda, who was ‘de passage’ in London. 8 years after the Egyptian revolution, I ask him how things are in Egypt, how the revolution might have affected him, the people, mental health and its youth.

Photo: Mo Homouda and Irena Grgona, Hampstead, London

Mo – an artist, physicist and film-maker – made the bold move to move to Cairo, Egypt, just as the revolution began in 2011, to write a screenplay. He has always been interested in hidden beauty and what makes people tick, especially under enormous pressure, on in seemingly hopeless situations.

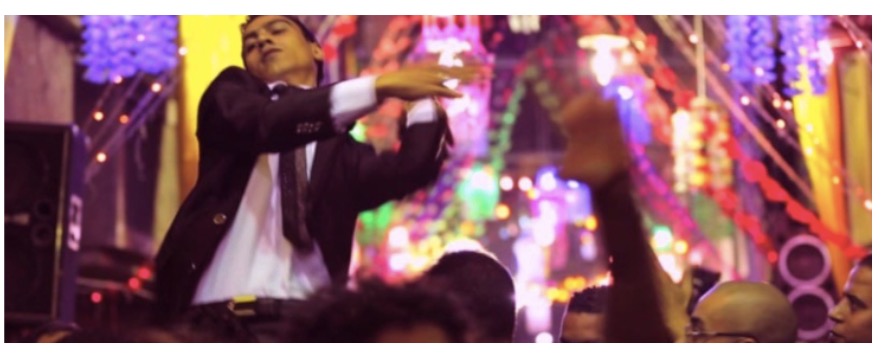

Photo credit: ‘Egyptian Revolution’, Cairo, Egypt

Not unlike explorers or ethnographers journeying into unchartered parts of the world, he paints deeply moving and eerie portraits of those he choses to focus his lens on; from the parents of an imprisoned Australian journalist arrested during the revolution, to the cross tattooing practices of Christian Coptic Egyptians. What his films (including “Switchblade”, “Hammer” and “Manicure”) have in common is the power of friendship, community, human resilience and seeing beauty in unlikely places.

Photo: “Switchblade” by Mohammad Homouda, Egypt

Irena: Mo, it’s been over 8 years since you decided to move to Egypt just as the Revolution started. Throughout that time you’ve been witnessing local lives and events, and making films on a variety of subjects. Looking back, what can you share with us? What’s it been like?

Mo: So much happens in 8 years, anywhere. But since January 2011, those first two or three years in Egypt were particularly dense. The political context is enormous and complex. By the time of the Arab Spring, President Hosni Mubarak had been in power for 30 years. He came from the Military, like all the presidents before him, so the Military and its interests have always been at the very centre of Egyptian power and leadership. 2011 had no shortage of upheaval, uncertainty and death. But it was also an extremely exciting and optimistic time. During those first 18 days of protests, and following Mubarak’s removal, there was an eruption of free expression, both political and cultural. But in 2013, after the coup and the ouster of the first democratically elected – albeit unpopular – President Morsi, the transition to democracy essentially came to an end. Then Abdel-Fatah El-Sisi, the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces took leadership (the Military took back power) and Egypt has since experienced a crackdown not seen in generations.

Photo: Dario Morandotti, Pyramids, Cairo, Egypt

One first-hand example is this: Before the coup, I was able to film in the streets freely without any real bother, let alone fear for my safety. Now it’s an entirely different story. Now, you’re reluctant to get your camera out in public, and getting permits is notoriously difficult. Before the coup, people were openly (and aggressively) criticising their leaders on television. Once El-Sisi took power, forget it. Those days were suddenly over. The atmosphere now is stifling and stressful. In place of all the optimism and expression, now I see a lot of malaise, a lot of people wanting to leave, and others just trying their best to focus on other things. It’s funny that we’re having this discussion at this moment. Right now we’re just days away from amendments being made to the constitution, that will extend the time allowed for El-Sisi to stay in power till as far as 2030. So things have come full circle and it’s difficult to imagine them changing any time soon. But I stay hopeful.

Photo: “ABC News Australia” Documentary by Mohammad Homouda, Egypt

(ABC News Documentary by Mo Homouda: Peter Greste was one of three Al-Jazeera English journalists who were arrested in Egypt in December 2013. Greste was held in prison for 400 days for the crime of “defamation of Egypt” and using “unlicensed equipment” to perpetrate it. When his parents visited him on Christmas Day 2014, I filmed their journey to Tora Prison, and interviewed them for the program, Foreign Correspondent)

Irena: How has this historic (maybe once in a life-time) experience changed you as a person and as an artist? Are you willing to share a little about your journey? The psychologist in me can’t help but see parallels between your (to quote Joseph Campbell) ‘ hero’s journey’ of inner transformation as a young man in his twenties to a more mature film-maker and man and parallels with Egypt’s own transformative and maturing journey?

Mo: Haha. Well, I turned 30 just a few months into my first year in Egypt, but, for sure, it was the kind of experience that undoubtedly leaves its mark. For me, the story of the revolution is a tragic one. As a child I’d only visited Egypt every other summer or so. Moving there in January 2011 was the beginning of my really getting to know the country, and it revealed itself to me over the next few years, with surprising turns along the way. In 2011 I thought everyone wanted the same thing. Freedom and justice essentially. Civil liberties. But in 2013 they handed that freedom back. Many many people, including relatives of mine, support this regime. There’s nothing eastern or exotic about this embrace of authoritarianism.

In the West we’ve seen it before and we’re seeing it again now. It’s really disturbing when it reveals itself amongst so many people around you, in the face of so much brutality. It’s been upsetting for a lot of people I know that have lived in Egypt their whole lives. So everyone has to learn to survive, mentally. In 2015/6 I found myself overwhelmed with anxiety, some of which originated from other things, but life in Cairo at that time really exacerbated it. It’s been very difficult for lots of people. I’ve had therapy and done a lot of work on myself to better deal with it. Beyond just being able to get out there every day and live a healthy life, for some of us it’s about how do we stay hopeful under these sorts of conditions? And what might resistance look like now?

Irena: In England we talk a lot about mental health, the rise of people suffering from depression, anxiety and more openness around breaking the stigma. Are you noticing any similar discussions in Egypt or in your profession?

Mo: Relative to the culture we’re used to in Europe, it’s not talked about in the same way. Mental health is more of a taboo subject than in the West. In some corners there’s discussion of the rise in depression and anxiety in Egypt following the counter-revolution. I’m no expert but I don’t think that good therapy is an option for many Egyptians. But amongst the middle class crowd that I’m familiar with, that are lucky enough to have some disposable income, there are good therapists available to them. I know many people that are seeing therapists and that are on medication for their mental health.

Irena: What would you want the rest of the world to remember about the revolution and to know about Egypt?

Mo: I guess I’d want the rest of the world to remember those first 18 days when a few very brave people inspired millions to join them, and they threw the powers that be off balance. Until it actually happens, it seems so improbably. But so long as you don’t give up, change could be just around the corner. And when it actually happens, suddenly the whole world looks entirely different. Possibility reveals itself. For that reason, I’ll always be grateful to have been in Cairo when Mubarak stepped down. It was an extremely powerful moment.

So for the second part of your question, I think I’d want the rest of the world to know that, despite what many people say, Egyptians are capable of – and deserve – freedom and democracy. Egypt is no longer a big story for the news outlets, like it was a few years ago. We’re back to having a deeply entrenched, self-serving, autocratic leadership that’s enabled by global powers. But if the past 8 years in Egypt have proven anything, it’s that when citizens organise and come together, they can really effect change. And I’m talking about citizens globally. We’re all citizens of interdependent nations, and we’re responsible for one another. So if you care about your own civil liberties, take a stand for everyone else’s.

Irena: What are you working on now and what’s next for you?

Mo: I’m back to developing fiction! Sometimes it’s easier to tell the truth with fiction. In Egypt people are often reluctant to speak candidly on camera about politics or social issues. I want to explore these issues as directly as I can, and reach as many people as possible. That’s how I see myself doing my part. It’s a bit of a minefield so … wish me luck!

Mo Homouda (www.mohomouda.com) makes films for a range of clients, from big corporates and NGOs to independent producers and news outlets. Work includes promotional material, documentaries and digital content. These films are produced to the highest technical standards by myself and a team of specialists. We’re committed to telling your organisation’s story in the most clear and compelling way.